It was inevitable…

… the scent of acetone always reminded Dr. Christian Dickel of the frustrations of nanofabrication.

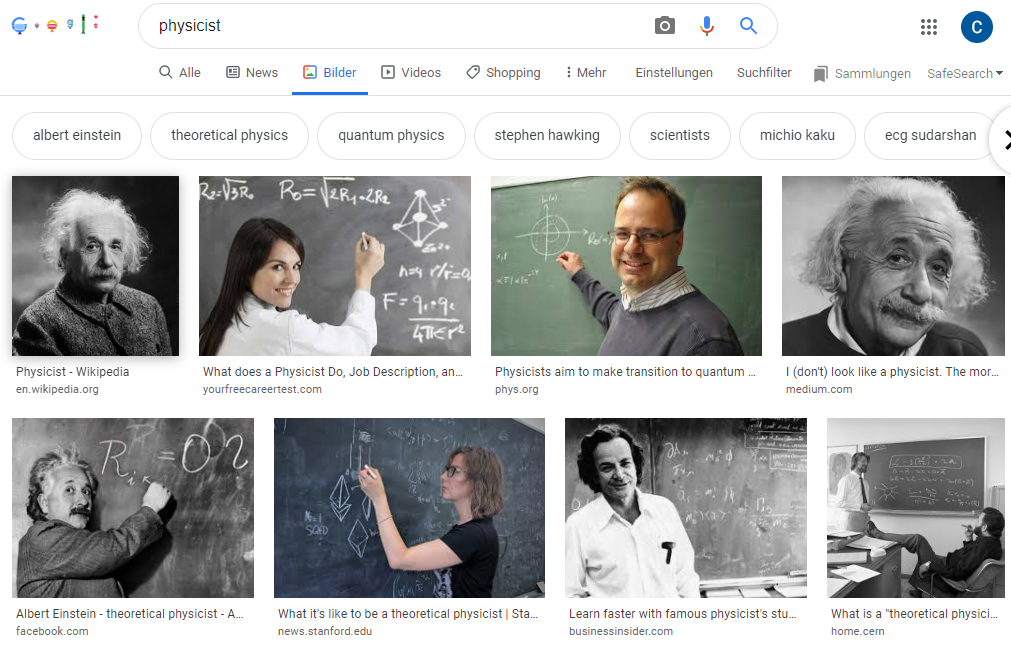

How does Covid-19 and the measures to mitigate the pandemic influence the life of physicists? Let’s start from what “normal” people think physicists do: A google image search of physicists gives a bunch of pictures of Einstein, people in front of blackboards (shout out to Frank Wilhelm for appearing so high on this google search!) as well as a picture of Einstein writing on a blackboard. The good news is, that in 2020 some of the people at the blackboards are women. Thinking and writing on blackboards can be done just as well during a pandemic! Didn’t Newton write the Principia while taking a black-plague-induced holiday in the countryside? So is everything fine?

Results on a google image search for physicist.

Well, no. Experimental physicists like me might be slightly less present in the collective consciousness than theorists, but while this time is difficult for everyone, keeping a lab running is more difficult than keeping up theory work. While we can automate a lot of task and remote log into computers, there are still some buttons that need to be pushed, cables that need to be connected by hand and nanofabrication has to happen in a cleanroom.

There is no universal physics-in-the-time-of-COVID-19 reality, so I will try to talk about mine. While I also often draw pictures on black or whiteboards when I discuss with colleagues, now I draw pictures in OneNote and share my screen on Skype or Zoom or Team Viewer. But this is not the biggest part of my daily life in the lab. For completely un-staged pictures of experimental physicists working in the lab, you should look at the ML4Q annual report, but in the following I want to give an account of pandemic challenges.

Keeping a lab going

In Andolab at University of Cologne where I am a postdoc, we try to realize protected quantum bits using exotic materials called topological insulators. Ultimately, the electronic wave function in those materials when combined with superconductors should give rise to Majorana zero modes. Those modes could become a new medium to store and process quantum information. This has been largely figured out theoretically, but testing theory and checking if this can be a valid technological platform comprises many hands-on tasks like nanofabrication, soldering, tinkering together cryogenic experiments and connecting the right cables to the right electronics at room temperature. Only if all practical challenges can be overcome does the theory really have merit.

So my colleagues that work on material synthesis are trying to keep molecular-beam-epitaxy machines running and we make their materials into computer-chip like devices that we cool down to really cold temperatures. Then we measure those devices and try to understand how they work and more importantly how we can store information in them. All of these things happen now, in the time of the pandemic, but we have limits on how many people can be in each room, we try to keep distance and we wear masks.

Basically, keeping complicated machines running and using them competently is a big part of the job, be it in nanofabrication, cryogenics or electronics. Most of this has to be done in a lab, so home office is not really an option. Only once everything is hooked up, cooled down and we take data and analyze it we can do things from home. Some tasks, like working with cold gasses or working with dangerous chemicals cannot be done alone for safety reasons. Luckily we already had a booking system in place for Machine time before the pandemic, this could then be used to coordinate to have enough but not too many people around for our tasks.

As much as managing our equipment in 2020 was made difficult by social distancing measures, delivery problems and the cooling water failures in the summer heat (which are noticed later because fewer people are there), nothing is more impaired than the most crucial part of every experiment: teamwork. Working in an effective team during the lockdown is quite a challenge. Our experiments rely on small teams of two to four people. We are using any channel known to modern man to communicate – phone, Skype, Whatsapp, Slack, Email, or coded messages in Git commits. Still communication and meetings are just a bit less effective than they would be in person. Knowledge transfer and teaching skills is especially difficult. Some of our manual machines, like a wire bonder (think something like a sewing machine), are best mastered by having someone who already works with them show the ins and outs of how to use them. Our job has some elements of a craft rather than just being an intellectual pursuit.

The Corona scare before Christmas

It was this knowledge transfer on practical matters that produced our first corona scare just before Christmas. I had worked in the cleanroom with a colleague because he was showing me how to do some of the processes he had developed – imagine the Harry Potter potions class. Now just after the day we had worked together he tested positive for coronavirus. In fact, the next morning he had lost his sense of smell. We had worn masks and had been in a ventilated cleanroom environment but I was naturally scared. The colleague as well as all of us who had come in contact with him went into two weeks of quarantine, which in our case precisely ended on Christmas eve. Our colleague couldn’t go home for Christmas because of travel restrictions but did not develop severe symptoms. All of us others got tested eventually and none of us had been infected. So it ended as well as could be hoped.

This experience still made me think more concretely about the risk evaluation of continuing our experiments and our teaching (in-person events such as exams, labs, having interns, bachelor and master students). The latter is easier to justify, we have students that depend on us trying to teach them, do labs with them, supervise their bachelor and master end projects, because those students deserve the same education as the people before and after them. We have to mitigate the negative effect on these enthusiastic young physicists because they are the future of our field. Still, supervising and correcting exams were the pandemic-time events where I was in a room with the most people.

How essential is our work? How essential is our happiness?

But what about the present of our field, to what extend shall we compromise on slowing down our experiments to flatten the curve? PhD students and postdocs have limited time contracts and while for the students the exam repeat requirements can be relaxed and BAFöG can be extended, our contracts cannot always be extended so easily. Being on a limited-time contract has definitely given me more anxiety during the pandemic time than ever before.

Thus, while our work is maybe not essential to society in any immediate sense (even if we would come out with a working quantum computer prototype right now, it is not going to take out the trash, take care of the sick or solve climate change immediately), our work is essential to us, because we need to produce results if we wish to continue on an academic path. It is also essential work to us in the sense that it can constitute who we are and be a calling rather than a profession. That being said, my wife is currently pregnant so we are trying to avoid contracting COVID. Almost all my in-person interaction with other people happens at work or in a supermarket. I do wonder if my work would justify the risk to me and my family. I don’t have a good answer and I don’t know to what extend I continue because I like working, or if I’m just used to it, or because I’m scared to not make the cut as an academic.

Personally, I struggle mentally with having less in-person discussions, both on data we just took and on what we should do next or even the bigger picture. These discussions and interactions with the team are a big part of what makes physics fun for me. So I am having a hard time to enjoy my job as much as I usually have. We had a few online conferences so far and while they are better than no conferences at all, I have to admit that I don’t engage with the information on the same level and I miss getting to know the other scientists personally. I cannot wait for things to go back to normal and hope I will have some postdoc contract at the end of the pandemic to enjoy the usual scientist lifestyle which made me want to stay in academia.

The upside of home office

The author in a bathrobe at the dinner table that has become his workplace. (c) Christian Dickel

However, measuring from home has some good sides. Here is a picture of my improvised desk at home. I originally thought I won’t need a workplace at home because I prefer leaving work at the office. Now, I have occupied our dinner table for almost a year. It is nice that our housecat occasionally visits me at work now or that I can eat lunch with my wife. Team viewer and remote desktop are very convenient and our admin team has taken care that the institute network has survived so many people logging in via VPN. Those admins are the heroes of this time! Our leadership at the university and institute level should maybe invest more in IT and have better options for home office in the future even beyond the pandemic.

We have run an experiment during the high time of the lockdown and corona measures and I think it measures up to experiments performed in more normal circumstances. Teaching has changed more as it completely moved online and my experience as a teaching assistant leaves me with mixed feelings. I did buy a writing tablet for teaching and it works well but I would prefer explaining things at a blackboard.

Image: Christian Dickel

About Chris

Chris got into this qubit stuff because he wanted to understand entanglement better. Now he works on topological quantum computing, so he has clearly given up on understanding things.