I have had quite an unusual career path, and it may be interesting for others to know that such a path is possible.

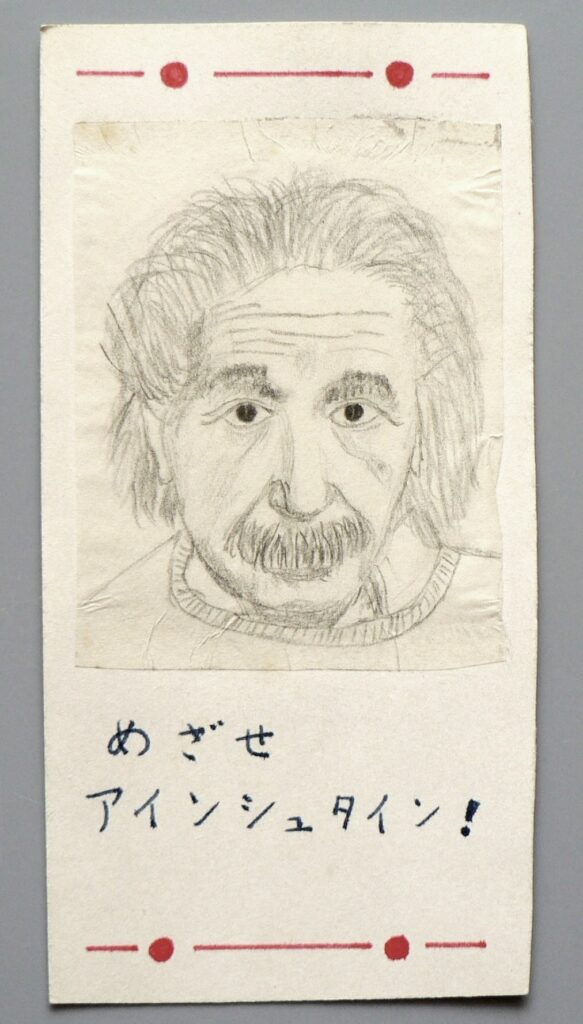

Yoichi made this bookmark and used it during his high-school days. Underneath Einstein’s face which Yoichi had to hand-trace himself due to the lack of a copy machine Yoichi wrote: 「めざせアインシュタイン!」, which means “Aim at Einstein!”

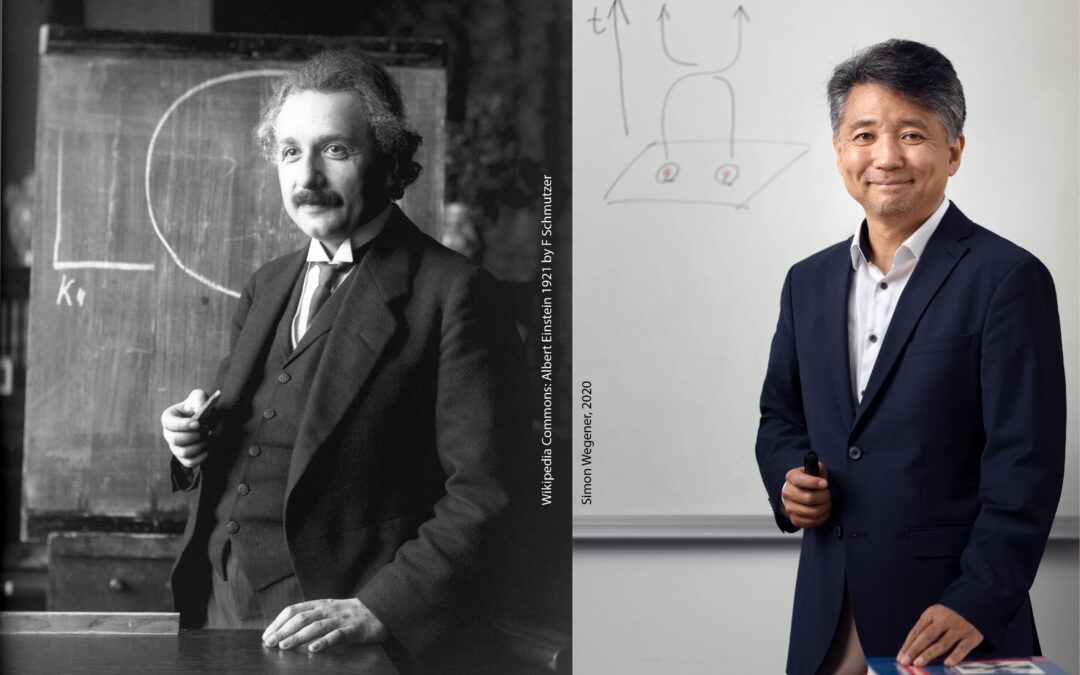

When I was a high school student, Albert Einstein was my idol. My dream was to become a physics professor (hopefully at the Princeton Advanced Institute) and unify the four forces. I was already learning special relativity on my own. Naturally, I joined the Department of Physics at the University of Tokyo, which offers the best chance in Japan for becoming an academic.

While I was a bachelor student, I studied advanced subjects (like general relativity, continuous group theory, quantum field theory, etc.) on my own. Also, since my plan was to become a physics professor in the US, I tried to use textbooks written in English as much as possible. For example, I used English textbooks on quantum mechanics by Shiff, quantum field theory by Bjorken-Drell, general relativity by Moller, mathematical methods of physics by Feynman, etc.

But when I joined the seminar on high-energy theory in the 7th semester (in Japan, bachelor education lasts 8 semesters), I realized that the high-energy theory to unify the four forces is no longer true physics, because the correctness of the theory cannot be proven by experiments. I was disappointed. I therefore decided to change my direction.

Just around that time, Prof. Klaus von Klitzing visited the University of Tokyo to give a colloquium, in which he essentially told us that if you are clever and lucky, you can hit upon a fundamental discovery to deepen our understanding of nature (and win the Nobel Prize). I was fascinated and decided to pursue a career in experimental low-temperature physics.

So I joined an experimental low-temperature physics lab to do my graduation experiment (there is no bachelor thesis at the Dept. of Physics at the University of Tokyo, because the professors there believe that physics is already so much advanced that bachelor students cannot perform any experimental nor theoretical works that would worth a thesis) and continued to do my master thesis in that lab.

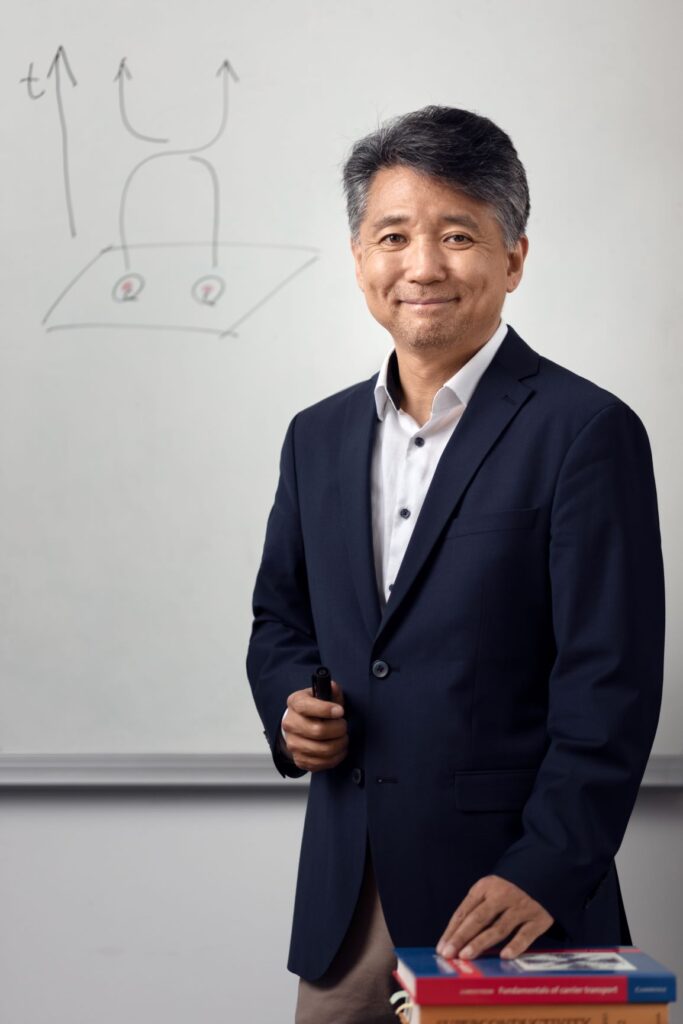

Sitting in his office in Cologne, Yoichi Ando’s eyes can always wander to Einstein’s poster hanging opposite to his desk and reminding him daily of his dream. (Image was kindly provided by Yoichi)

The topic of my master thesis was mesoscopic physics in superconductors. However, the lab was not sufficiently well equipped to perform experiments that can be competitive in the forefront of mesoscopic physics. I was disappointed and worried that I would not be able to perform worthy experiments for my PhD thesis in that lab. I therefore decided to quit the graduate school after getting the master’s degree and joined an industrial research institute in 1989. At that point, I gave up my dream to pursue an academic career in fundamental physics.

I was disappointed and worried that I would not be able to perform worthy experiments for my PhD thesis in that lab.

In that research institute, named Central Research Institute of the Electric Power Industry (CRIEPI), I joined a group to pursue the application of superconductivity to ac power transmission. I did some theoretical work in that project for two years, and then in 1991, I was dispatched to a relatively new laboratory founded by the Japanese government to foster the research on high-temperature superconductivity, which was discovered two years ago (in 1989). The name of the lab was Superconductivity Research Laboratory (SRL), the director of which was Prof. Shoji Tanaka, who was known in the community for his confirmation of the claim of Bednorz & Müller to have discovered a potential high-temperature superconductor in the La-Ba-Cu-O system. When I joined SRL, I was somehow hand-picked by the director to work nominally under his direct supervision, which means that I was able to work independently on whatever topic I wanted to investigate. This gave me the opportunity to return to the academic path. I chose the topic of vortex dynamics in high-temperature superconductors (HTSC) for my research at SRL, because it was a hot and growing field at that time, with the discoveries of new concepts such as vortex-glass transition, flux-lattice melting, collective pinning, macroscopic quantum tunneling, etc. I built the necessary facility to perform experiments on the mesoscopic effects in vortex dynamics, and these experiments were quite successful. Based on these experiments, I wrote my PhD thesis on my own and got the PhD degree from the University of Tokyo. I also had the opportunity to present my work in the US at a conference, and on that occasion I visited the Bell Labs (in New Jersey) and the IBM T.J. Watson Research Center (in New York) to give seminars.

As a result of these visits, I was given the opportunity to do my postdoc at Bell Labs in the laboratory of Greg Boebinger, who had built a 60-T pulsed magnetic field facility at Bell Labs and was trying to use this facility for the fundamental research of HTSC.

I built the necessary facility to perform experiments on the mesoscopic effects in vortex dynamics, and these experiments were quite successful. Based on these experiments, I wrote my PhD thesis on my own and got the PhD degree from the University of Tokyo.

Therefore, although I was already beginning to be known in the field of vortex dynamics, I decided to change my topic for my postdoc work to pursue the mechanism of high-temperature superconductivity. Together with Greg Boebinger, we discovered that the normal state of HTSC in the underdoped regime is actually an insulator when the superconductivity is suppressed by a high magnetic field. We furthermore discovered that there is a metal-insulator crossover near optimum doping, which triggered the development of the concept of a quantum critical point governing the physics of HTSC. We published a series of high-profile papers to report these discoveries and we both became well known in the HTSC community. Sometimes our contribution is called “Ando-Boebinger experiment”. Greg Boebinger developed his career nicely based on this contribution, and he is now the Director of the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory of the US.

After two fruitful years at Bell Labs ending in 1996, I returned to Japan and led a research group at CRIEPI to work on HTSC. This was because I was (again) hand-picked by the President to pursue fundamental physics to establish the visibility of CRIEPI in basic research. My strategy at CRIEPI was to become the best in the world in the growth of high-quality single crystals of HTSC and build a world-wide network of collaborators. At the same time, we performed the most accurate and systematic measurements of the transport properties of HTSC. My group was actually very successful and CRIEPI became well known in the HTSC community. But after the President of CRIEPI changed, my research direction was less appreciated and the institute wanted me to serve in the management, which I didn’t like. So I decided to move to a university.

Once again, I decided to change my research direction, and I chose to work on topological materials. That was a right decision.

Yoichi’s vision is to soon prove Majorana braiding and provide a game changer in quantum computing hardware.

I was appointed a full professor at Osaka University in 2007. In Japan, universities provide no start-up funding, and it is the responsibility of a newly appointed faculty to raise sufficient third-party funding to equip their lab. In 2007, the high-temperature superconductivity was already considered to be an overhyped and unproductive problem and it was difficult to obtain large-scale funding for high-temperature superconductivity. Once again, I decided to change my research direction, and I chose to work on topological materials. That was a right decision. I became one of the pioneers in this new field and I was able to obtain a series of large-scale funding on this topic in Japan. But I became increasingly more frustrated at the research environment of a Japanese university (because the Japanese government kept decreasing the basic budget for national universities) and eventually decided to move to a foreign country. I was invited to interviews at various universities in the US, Canada, and Europe. The University of Cologne was the first university which came up with an offer to satisfy my requirements, so I decided to come to Cologne.

After coming to Cologne in 2015, I decided to make yet another change in my research direction. This time, I decided to pursue mesoscopic device physics to investigate the fascinating non-Abelian nature of Majorana zero mode in topological superconductors and its application to topological quantum computing. It is interesting that I (sort of) came back to the topic of my master thesis, mesoscopic superconductivity. But this time, I am well equipped. Moreover, the framework of ML4Q enhances my chance of success through fruitful collaborations. I am quite positive that we can make fundamental contributions to the development of topological quantum computing and leave the name of ML4Q in the history of quantum technologies.

It is interesting that I (sort of) came back to the topic of my master thesis, mesoscopic superconductivity. But this time, I am well equipped.